Measurement: Length, width, height, depth

Length, width, height, depth

Outside of the mathematics class, context usually guides our choice of vocabulary: the length of a string, the width of a doorway, the height of a flagpole, the depth of a pool. But in describing rectangles or brick-shaped objects, the choice of vocabulary seems less clear.

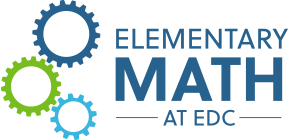

Question: Should we label the two dimensions of a rectangle length and width; or width and height; or even length and height? Is there a “correct” use of the terms length, width, height, and depth?

Rectangles of various shapes and positions.

The choice of vocabulary here is entirely about clarity and lack of ambiguity. Mathematics does not prescribe rules about “proper” use of these terms for that context. In mathematics as elsewhere, the purpose of specialized vocabulary is to serve clear, unambiguous communication. In this case, our natural way of talking gives us some guidelines.

Length: If you choose to use the word length, it should refer to the longest dimension of the rectangle. Think of how you would describe the distance along a road: it is the long distance, the length of the road. (The words along, long, and length are all related.) The distance across the road tells how wide the road is from one side to the other. That is the width of the road. (The words wide and width are related, too.)

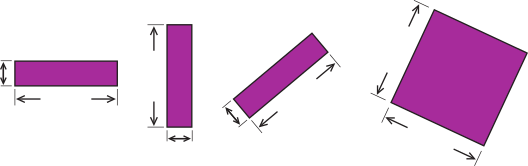

When a rectangle is drawn “slanted” on the page, like this, it is usually clearest to label the long side “length” and the other side “width,” as if you were labeling a road.

Slanted rectangle.

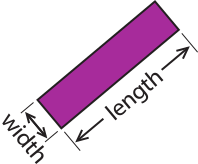

Height: When a rectangle is drawn with horizontal and vertical sides, the word height makes it clear which dimension is meant; height labels how high (how tall) the rectangle is. That makes it easy to indicate the other dimension—how wide the rectangle is from side to side—by using the word width. And if the side-to-side measurement is greater than the height, calling it the length of the rectangle is also acceptable, as it creates no confusion.

Rectangles of various orientations.

Notice that in this case, when height is used, the comparative size doesn’t matter. Because height is always vertical, either measurement, width or height, can be greater.

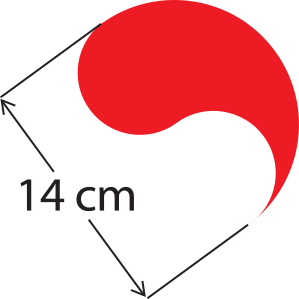

For some non-rectangular shapes the terms length, height or width would remain unclear, show explicitly what you mean  and refer to it as “this distance” or “this measurement.”

and refer to it as “this distance” or “this measurement.”

Three dimensions

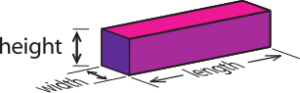

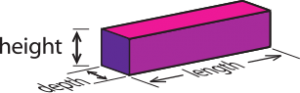

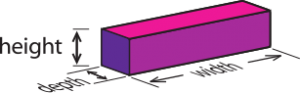

When naming the dimensions of a three-dimensional figure, the only rule is make sense and be clear. It will help to use labels.

When the figure is “level,” height clearly refers to the vertical dimension—how tall the figure is—regardless of whether that dimension is greatest or least or something in between; length (if you use the word) refers to the longer of the other two dimensions. But you may also refer to the other dimensions as width and depth (and these are pretty much interchangeable, depending on what “seems” wide or deep about the figure). See these examples.

When height would be unclear—for example if the figure is not “level”  —people cannot know what is meant by width, depth, or height without labels, although length is generally still assumed to refer to the longest measurement on the figure. And, as in two dimensions, terms like “length,” “width,” and “height” won’t feel natural or be clear for some shapes, like a tennis ball.

—people cannot know what is meant by width, depth, or height without labels, although length is generally still assumed to refer to the longest measurement on the figure. And, as in two dimensions, terms like “length,” “width,” and “height” won’t feel natural or be clear for some shapes, like a tennis ball.

What’s in a word?

Length, width, height, and depth are nouns are derived from the adjectives long, wide, high, and deep. They follow a common English pattern that involves a vowel change (often to a shorter vowel) and the addition of th. (The lone t in height is modern. Obsolete forms include heighth and highth, and it is still common to hear people pronounce it that way.)

| wide | deep | high | long | broad |

| width | depth | height | length | breadth |

Other English adjective-noun pairs are related in this way, too: e.g., hale as in “hale and hearty” and health (but hale, except in that expression, is now mostly replaced by “healthy”).